Alan Muchlinski looked out his window in the 1990s and knew something was wrong. There was a squirrel in his West Covina backyard that wasn’t supposed to live in Southern California. An Eastern fox squirrel – not the native Western gray – was eating from his apricot tree. The grays don’t like the taste of fruit, but the Easties are indeed a different story.

It’s two squirrels in SoCal. One local, one imported. One, a big fluffy-tailed specialist with a penchant for pine trees and tree nuts that used to rule the roost in SoCal. The other, a red-furred sleek generalist from the East Coast, a fast procreator with an appetite for everything. To call this a mismatch would be an understatement.

As a biological sciences professor at Cal State LA, Muchlinski took on the task of discovering how this non-native species was affecting SoCal’s resident Western gray, a critter that hasn’t been under the microscope much. It’s a squirrel, after all, a taken-for-granted species that doesn’t have the powerful draw of a mountain lion or big-horned sheep.

“So many people would say, ‘What’s the big deal? One species replacing another? What does it matter?’ But the reality is introduced species cause problems with the natives and affect the ecosystem,” he says. “We just don’t know what the complete consequences are.”

The frisky Easties found passage to Los Angeles around 1904 to the Veteran’s Hospital in West LA where they were “pets” to residents. At first, no one seemed to mind when a few escaped into the ‘wild’, but then damage to local fruit and nut trees became apparent and the pets quickly turned into pests.

Henry Huntington also put out the call to import Easties into his nascent San Marino Gardens for atmosphere flavor (unfortunately, they were DOA on the local train).

Through the years, Muchlinski has been a faculty advisor to many grad students wanting to uncover more details about Squirrels in Our Midst.

In 2004, graduate student Julie King, tracking Easties distribution patterns in SoCal, discovered many folks were trapping and dumping them in other locations thus exacerbating the bigger problem. Easties followed human development and slowly made their way along SoCal lowlands, setting up shop while grays in their pathway, quietly retreated into pocket populations.

Even with a few studies on the grays, it’s apparent their numbers are decreasing.

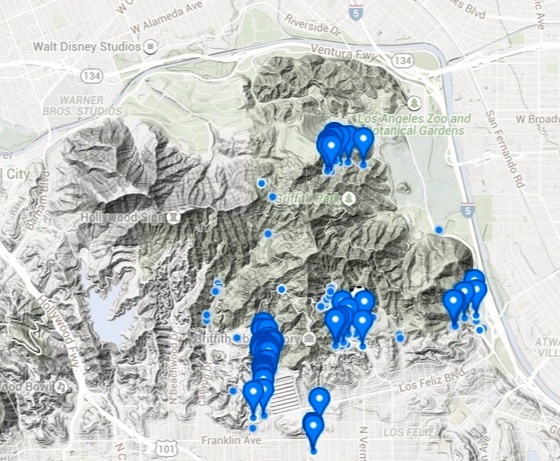

Today, Muchlinski is faculty advisor to another grad student, Chris DeMarco who has been immersed in the squirrel world for three years; his thesis project involves collecting and interpreting genetic samplings of gray populations. He’s targeted populations in the Santa Monica Mountains, Griffith Park and Rancho Santa Ana Botanical Gardens. Within those areas – especially Griffith Park – grays have become isolated into smaller subgroups.

“Gray squirrels are also an indicator species of how well a natural oak/conifer habitat is doing,” says DeMarco walking through Griffith’s Ferndell. The fluffy mammal also plants trees (hiding/forgetting nuts and through their feces); they also eat a particular fungus that, when dispersed through their feces, allows oak and pine tree roots to better absorb water.

Ferndell is just one Griffith Park area on DeMarco’s radar. Grays have been found in Boy’s Camp, Vermont Canyon and the Roosevelt Golf Course. He enlists help from citizen scientists who record observations via I Naturalist to find squirrels for his studies.

DeMarco collects genetic material from strategically placed “hair tubes” that are stuffed with walnuts and other squirrel delights.

When the critter enters to enjoy an easy meal, some of its hair brushes up against sticky tape inside the tube and is left in the tube. These hair follicles contain DNA which DeMarco uses to chart lineage of the grays, estimating how genetically diverse these populations are and if there is any genetic flow between populations.

Comparing gray maternal genetic profiles in Griffith Park, DeMarco is discovering disturbing trends – basically, gray squirrels’ genetic makeup is similar because they are inbreeding. Even though squirrels are known for their acrobatics and wire walking abilities, the grays find it difficult to branch out beyond their original homes. Traffic and human development keep them stuck. Besides isolation, grays are up against other factors: poisons, roadkill, destructive fires and competition with the Easties.

“Studies have shown it’s possible for grays and Eastern fox squirrels to coexist,” says DeMarco explaining that in areas with a wide diversity of tree species – like Ferndell – there is a higher proportion of Western grays. “There could be a way to sustain these two species if there were more pine, walnuts and sycamore trees in the area, trees the grays like. Here in Ferndell, grays and Eastern fox squirrels seem to coexist for the most part.”

But the question is for how long? Muchlinski isn’t sure, but he does know that if the Easties move into SoCal’s forested areas – Big Bear, Mt. Wilson – that could be catastrophic for SoCal grays. “It helps if people understand that it’s not good to move non-native animals around,” he says.

All in all, Griffith Park is snapshot of SoCal squirrel-ness. “By seeing what is happening here, we can start to target and suggest ways to circumvent any potential extinctions of one of the sub populations,” says DeMarco. “If populations become so isolated and are in a dire downward spiral, it may mean special action.” Conservation possibilities: adding more gray-friendly trees, introducing grays from other areas into that population to beef up the gene pool, and create corridors for squirrels to scamper in and out of isolated habitats.

When his research wraps up next year, DeMarco will share it with local agencies like LA Park and Rec, National Park Service, etc. “Genetic studies have been done on the gray squirrel in Washington and Oregon but not here,” he says. “We, California, need to catch up.”