Walking into the expansive space at the current exhibition, “Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent” at the Pasadena Museum of California Art feels as if you are entering a fresh new world of a present-day artist whose powerful images speak of big issues and spiritual intimacies.

How times have — and have not — changed.

The exhibition — on display until Nov. 1 — is the first full-scale retrospective that spans 30 years of work from Kent, an Immaculate Heart of Mary sister and artist/instructor at the Immaculate Heart of Mary College in Los Angeles from 1947-1968; she eventually left the religious order and kept practicing art until her death in 1986.

After showing in five other cities — including at the Andy Warhol Museum in Pittsburg — the traveling exhibition comes back to Los Angeles and features hundreds of images culled from the Corita Art Archives at the IMH campus as well as pieces from private individuals and museum collections. The exhibition also includes rarely shown photographs Kent used for teaching and documentary purposes.

In the past, some of Kent’s iconic prints and groundbreaking designs have been included in other larger art exhibitions, but this show is a walk through the artist’s life via her artwork. It’s all Corita Kent.

In the gallery, Kent’s early religious images, like those of the Madonna and Child, give way to bold brilliant colors with imagery and lettering fonts taken from advertising, newspapers and other formats which eventually yield to reflective watercolors of simple, quiet beauty.

Kent is probably best-known as a pop artist (such as her “Love” stamp design for the U.S. Postal Service) and/or a social activist in the 60s (which got her on the cover of Newsweek as “The Modern Nun,” much to her disdain), but her overall work reveals an intricate weaving of personal thoughts and musings on the nature of spirituality, faith and humanity.

“She reflects on what is going on around her in the world — like war, hunger, conflicts, civil rights — and other times, she’s reflecting on her own journey or those close to her, such as her students, family and friends,” says Ian Berry, exhibit co-curator and Dayton Director of the Frances Young Tang Teaching Museum and Art Gallery at Skidmore College in New York.

Berry is proud the exhibit features two of Kent’s full alphabets, the Circus Alphabet and Signal Code Alphabet, large-scaled multiple art pieces that explode with color and font, imagery and ideas. “Some letters are funny, some are serious,” he says. “These are really some of her master work.”

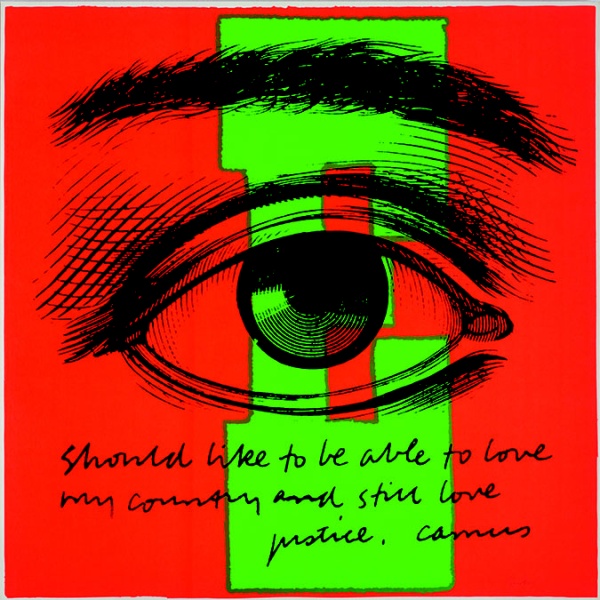

Indeed, Kent’s layered work invites viewers for a closer look. “You see the piece at a distance, big and bold, but then as you get close you discover more,” says co-curator Michael Duncan of the handwritten citations with quotes, passages and personal thoughts that are a hallmark of her work. “This is not two-second art, she engages viewers into her world.”

Duncan describes Kent’s love of the written word and how she drew from a wide variety of literature and poetry, inspired by creatives who, like her, saw the wonders, struggles and spirituality of life. One didn’t have to be Catholic or even Christian to appreciate her sensitivity and expressions of faith.

“Using the medium of printmaking was also revolutionary for the times,” points out Duncan; prints were usually considered second-class art, but in Kent’s hands, they became dignified and noteworthy. In addition, printmaking also appealed to Kent’s democratic sense that art is for the masses and images were meant to be spread around.

During the course of putting the exhibition together and following its travels, Duncan and Berry have met former students who have great memories of being under Kent’s tutelage, despite her grueling assignments.

Her “impossible assignment” required students to reproduce a simple object or create a collage 100-plus times. “She was trying to get the students to break down their pre-conceived notions of what that object meant and would tell them by the 65th try, they were just starting to see the thing,” says Duncan. “Corita wanted to take them to the next level of seeing.”

The overriding goal of this exhibition, explained Duncan and Berry, was to secure a spot in art history for Kent and to introduce her art to new generations.

Indeed, the world may be ready for more Kent. After the conclusion of this exhibition, Harvard Art Museum, in partnership with the Barbara Lee Family Foundation, will be staging “Corita Kent and the Language of Pop” in September 2015; that show will also be on display next year in Berkeley and San Antonio.

“So often, art critics dismiss art that is openly spiritual as well as works that infuse humor and a sense of playfulness,” says Duncan. Far from being a pop Pollyanna, Kent had a deep sense of wonder and joy for the world, even when her work reflected troubling and tragic aspects of humanity. “She embraced it all.”

A variety of educational programs are slated at the Pasadena Museum of California Art for “Someday is Now: The Art of Corita Kent” including a play reading about her life “Little Heart” at All Saints Church in Pasadena (July 18), curator’s walkthrough (July 19), children’s bookmaking workshop (July 25), family day art projects (Aug. 1) and more. Check the PMCA website for details.