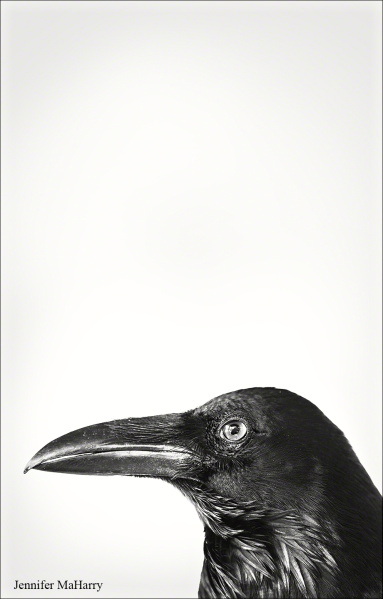

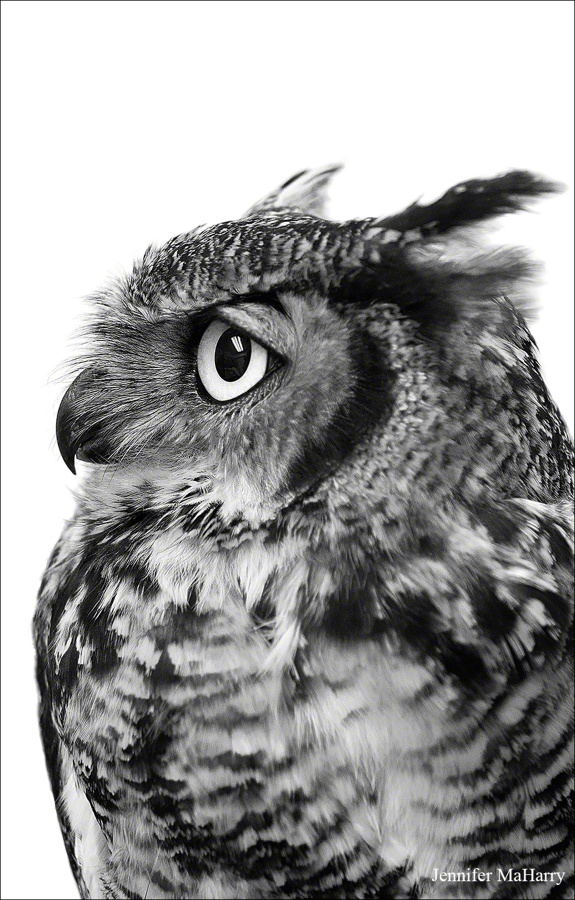

Countless birds fly under the radar in the Endangered Bird World these days. Many birds don’t get the full court press like their flashier “rock star” cousins, flappers that require extraordinary measures to ensure their survival in the wild.

We hear about the superhuman efforts (and big $$$) to save the California condors, bald eagles and other notable birds; scaling the sides of mountains to remove viable eggs, creating floating islands so mama birds can safely nest, closely monitoring every movement, flight and meal in the wild. Some birds are almost living a Truman Show existence.

But consider the Belding’s Savannah sparrow – a seemingly innocuous, unassuming federally threatened state endangered bird that has managed to eke out survival in one of L.A.’s seriously decimated habitats: the coastal salt marsh. “Based upon the 2010 surveys, Belding’s are doing well within their range in California,” states the most recent report by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife on the bird which was surveyed from Goleta to Baja, Mexico. “This is the highest state total reported since periodic counts began in 1973,” sums up the report.

(An Acrobatic Belding’s Eyes the Territory…Photo by Matt Sadowski)

Since 1973, the numbers of Belding’s have increased three-fold statewide despite that its’ preferred home has shrunk considerably from its once majestic acreage.

Bits and pieces are all that remains of the once giant coastal salt marshes that stretched from Santa Barbara County to Mexico. It’s estimated that today we’re only seeing between 5-10 percent of the marshes that once bogged the area. Dredged and bulldozed over for development, it’s a wonder we have anything left of these soupy prairie-like lands where wildlife – especially birds – flock.

The remarkable story of the Belding’s Savannah sparrow is how closely intertwined the bird is with the landscape. Coastal salt marshes are the ONLY place you’ll find this bird and they are not known for migrating from marsh to marsh. They live, eat, mate, nest and die in pretty much the same neighborhood. They create strong family units with hatchlings and even dad helps take care of the young.

The last remaining coastal wetlands in Los Angeles County, the Ballona Wetlands Ecological Reserve in Playa del Rey has been a consistent home to a small but plucky group of Belding’s that just wants to keep peace among sea-blite, salt bush, salt grass and, its favorite plant, the pickleweed that, like the bird, is only found in salt marshes.

(The Ballona Wetlands today….photo: Friends of Ballona Wetlands)

This little songbird didn’t require conservation acrobatics to stabilize its population – the needs of the Belding’s were simple: pickleweed, seeds, insects, a mate and…. oh, yeah….a coastal salt marsh. An endangered bird in an endangered landscape.

Considering the cost of what it takes to bring back other species, the Belding’s is “a bargain bird,” says biologist Dan Cooper who has recently surveyed and reported on the birds’ current state of affairs at Ballona. “The land is the thing for the Belding’s’,” he says. “They have a little stable population there without any real management to speak of but they are a real conservation success story.”

“There were about 13 pairs in the late 80s and now we are seeing about 20 pairs,” says Cooper who adds that numbers have fluctuated up and down over the years but they are steadily trending upward. “With the pickleweed expanded in recent years, so has the population of Belding’s.”

Cooper says that no one really has studied the mortality rate of the youngsters. After all, these birds are fighting non-native red foxes and domesticated cats and dogs that find their way into the reserve. If Fido and Fluffy are kept at bay, who knows how many more Belding’s may grace the wetlands? Probably a lot more. Homeowners: take note.

(House cats roam Ballona…Photo by Martha Benedict)

“There is certainly room at Ballona for more Belding’s,” says Cooper. “The land can accommodate them.”

“They are cute little strappy guys,” says Kathy Keane, biologist who surveyed the Belding’s from 2006-2010. “They seem so much in their element when I observed them,” she says describing how the birds’ nest and care for their young from about late April through August.

(Strappy Enough for You?….Photo by Matt Sadowski)

Keane talks fondly about the songs that the male sings to the female during mating and the occasional altercation between males when they have a “fluff-up face-off.” Even with the roar of airplanes overhead, traffic from nearby boulevards and predation, “These birds manage to go on with their daily lives,” she says. “They are really persistent.”

Indeed, both bird and landscape have tenacity for…well, just being here.

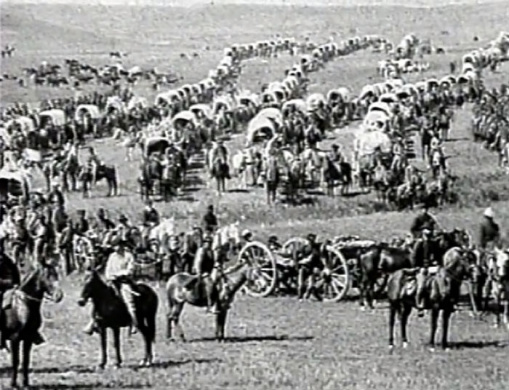

The Belding’s hopeful story mirrors the hope for the revitalization of Ballona landscape which has been constantly changing since European settlers embraced the area decades ago.

Over the years, this once-lush wetland has been a cattle ranch, a race track, agriculture plots, a recreational boating and fishing site, a riding stable, a massive oil rig operation and an airport runway. In the 1950s, the Army Corps concreted over many of the nearby springs/creeks that fed into the area. In the 1960s, 900 acres of wetlands was destroyed for the construction of Marina del Rey.

(Grazing Livestock at Ballona in the 1800s…Photo from Friends of Ballona Wetlands)

When scientists, environmentalists and citizens woke up and smelled the burnt coffee in the 1990s, they realized that in exchange for roads, apartment building and shopping centers they had, for all practical purposes, killed freshwater ponds, vernal pools, wet meadows, freshwater marshes and numerous springs. Efforts to save what little of the Ballona was left kicked into high gear.

Today, the Ballona landscape is set to change once more. The reserve has been owned by the State of California since 2003; the area is managed by Fish and Game with the California Coastal Conservancy and the California State Lands Commission part of the equation; the volunteer-basedFriends of Ballona Wetlands also has a stake in the upcoming discussion about tidal flushing.

(Ballona Landscape…Photo by Martha Benedict)

A true wetland would have regular tides coming in and out giving the area a good salt water bath which would help the pickleweed and other plants grow – but such flooding could mess up nearby Culver Boulevard not to mention the Belding’s’ and other species garden level habitats. It’s not just a question of “To Flush or Not To Flush,” but how much, when and where. In addition, some Native Americans are also concerned about disturbing land that they claim is sacred. Stay tuned.

Until that decision comes, life continues for the birds of Ballona. On a recent August morning, the Belding’s weren’t coming out to sing since mating season has long past, but you could scan the expansive marshland and see the pickleweed tips turn summer red. Mockingbirds, herons, gulls, pelicans and other flappers take to the skies above.

(Pick a Patch of Pickleweed…Photo by Martha Benedict)

Thriving only in a salty habitat, the Belding’s continued presence at Ballona may not be the heart-pounding, high-stakes conservation story of some of its feathered cousins. But its’ tale is just as profound: when given the right conditions – aka, space and freedom – nature can quietly reclaim both landscape and critter as one, bringing back into the fold what was once lost.

(Ballona Trailer Art…Photo by Martha Benedict)

– Brenda Rees, editor

Special thanks to Karina Johnston, restoration ecologist of the Santa Monica Bay Restoration Commission, Kathy Keane of Keane Biological Consulting, Dan Cooper of Cooper Ecological, and Lisa Fimiani of the Friends of Ballona Wetlands.